The Representing the Unseen exhibition captures the many foundational themes and histories of Latin American art. The several bodies of land that make up what we consider Latin America today were built on perspectives and traditions from different parts of the world. From Indigenous and African ideas to women of marginalized communities, Representing the Unseen dissects who and why certain groups are historically omitted from artistic narratives. By shining light on the exact art pieces and voices that are perpetually shunned, audiences are exposed to certain ideologies that, although seemingly new and innovative, have existed throughout Latin America for centuries. Curated to mirror the Andean Indigenous cyclical understanding of space, time, and life, each piece and theme in Representing the Unseen is in conversation with one another. There is no linearity or precision within the art and belongings because the principles of influence do not manifest themselves in that way. Representation of the unseen immerses you in Latin American art history: the real one.

Welcome to Representing the Unseen, my second ever curatorial endeavor.

This version of Representing the Unseen has been augmented to fit the style of the blog and encapsulate the physical experience of the exhibition digitally.

Representing the Unseen

Curated by Avery Vilela

The Representing the Unseen exhibition captures the many foundational themes and histories of Latin American art. The several bodies of land that make up what we consider Latin America today were built on perspectives and traditions from different parts of the world. From Indigenous and African ideas to women of marginalized communities, Representing the Unseen dissects who and why certain groups are historically omitted from artistic narratives. By shining light on the exact art pieces and voices that are perpetually shunned, audiences are exposed to certain ideologies that, although seemingly new and innovative, have existed throughout Latin America for centuries. Curated to mirror the Andean Indigenous cyclical understanding of space, time, and life, each piece and theme in Representing the Unseen is in conversation with one another. There is no linearity or precision within the art and belongings because the principles of influence do not manifest themselves in that way. Representation of the unseen immerses you in Latin American art history: the real one.

- AV

Welcome to Representing the Unseen

This gallery was designed to mirror the Andean Indigenous cyclical understanding of space, time, and life; each piece and theme in Representing the Unseen is in conversation with one another. You are invited to begin your experience anywhere in the space. There is no “correct” starting point. The layout reflects a blurred concept of linearity—encouraging you to explore freely and make your own connections between the works.

Next to each artwork, you will find two didactics:

The Curatorial Label — Provides contextual information and a description of the work. These labels include the title of the piece and are placed directly under the artwork.

The Read — This is a short, informal reflection or personal take on the artwork. Some art spaces have begun incorporating reads to bring new voices into the gallery conversation. All the reads are my own commentaries, offering how I see or relate to each piece. These appear after the curatorial label and do not include the title.

Feel free to engage with the art in whatever order feels right to you. Follow what draws your attention, revisit works, and spend time where it resonates.

Thank you for being here,

-AV

Guaman Poma

La Primera Historia de las Reinas Coya Mama Huaco Coya [La Nueva Corónica]

1615

Guaman Poma, an Inca nobleman working in the Viceroyalty of Peru, worked on a project with other Inca to form a 1,189-page book composed of thousands of words and hundreds of drawings. Titled La nueva corónica, this visual amalgamation of the Inca perspective was originally written with the purpose of being sent to King Philip III of Spain to inform him on how colonization had truly affected Andean civilizations. Written in a combination of Quechua, Latin, and Spanish, La nueva corónica is a true representation of Mestizaje and its effects. La Primera Reina Coya Mama Huaco Coya, translated to “The first Queen Coya Mama Huaco Coya”, was a very important figure to the Incas due to her fascinating history. According to Guaman Poma and on the account of the Inca people, La primera Coya was a beautiful, dark-skinned Queen and daughter of the Gods who had the power to speak to the rocks and the guaca idols. La primera Coya was praised and adorned by all and died in her land at 200 years old.

.

In protest

of the

two colonial languages of Spanish and English, the formation

of my words is in the shape of the principal way of communication

for the Inca. Commonly used for record keeping of important dates, census numbers, and narrative information, the quipu is a complex system of knots

created with cords and pendants. Unlike European communities, many indigenous Andean civilizations did not use writing as a form of preserving history. Rather, they used different creative forms that had ties to spiritual and land identities. This visual composition of one of the many modes of communication used by the powerful Incas serve as a window into the brilliance and originality of their quotidian lifestyles.

Guaman Poma

El Decimo Inga Topa Inga Yupanqui [La Nueva Corónica]

1615

Included in Guaman Poma’s extensive letter is his account of the royal Inca lineage. He discusses the divine nature of the rulers of the Inca with dialogue and drawings to express different modes of communication in hopes that one of them would capture the Inca perspective best. El Decimo Inga Topa Inga Yupanqui translates to “The Tenth Inca Topa Inca Yupanqui”. According to Guaman Poma, El Decimo Inga Topa Inga Yupanqui was a gentleman who was extremely knowledgeable and ruled with peace; he traveled to many different lands and worked closely with his people to ensure their comfort and safety in their neighborhoods.

Also mimicking

the Inca

way of communication, this

Quipu serves as an explanation for the

lack of italicizing for both Guaman Poma prints.

The act of italicizing titles in the

art world is to identify a particular piece

as a work of art.

The reason why these two pieces are not italicized

is that they are not limited to just being art, but illustrations of the Inca way of life during colonization. As stated

in the information above, these two prints are a

part of Guaman Poma’s extensive letter to the king of Spain— whose name is irrelevant as this is an Inca narrative, not a Spanish one— and because writing

was not an Inca way of communicating, he deemed it necessary to create visuals to support his words

further. The titles are unitalicized to inform that, although visually appealing, understanding the intentions of the creator

is of the utmost importance to truly understand

what you are looking at.

Uncredited Mestizo Artist(s)

Virgin of Pomata with St. Nicholas Tolentino and St. Rose of Lima

1700-1750

This painting depicts the Virgin of Pomata, a revered icon of the Virgin Mary in the Andean region of South America. The Virgin of Pomata's iconography is a blend of European and Indigenous Andean traditions, reflecting the cultural exchange during Spanish colonial times. Although created with the intention to spread Catholicism and replace the Indigenous religions, there are several Inca symbols within the painting. For example, the Virgin herself. Her shape reflecting the Andean mountains is an Inca-significant detail incorporated by Mestizo artists to protest this cultural erasure through Catholic artistry.

Under the limited information provided by the Brooklyn Museum on any painting from the Cuzco School, you see the words, “Donated by Frank L. Babbott”. Who is Frank L. Babbott, and why is he the sole donor of all Cuzco School pieces owned by such a renowned art institution like the Brooklyn Museum? Babbott was an American collector, merchant, and philanthropist who lived from 1854 to 1933. What you need to know is: Frank L. Babbott went to Peru, found a way to take 8 works of art containing the history of Mestizaje from the land, brought them to New York, and gave them all to the Brooklyn Museum with virtually 0 information. Think about that.

Uncredited Mestizo Artist(s)

Saint Joseph and Christ Child

Late 17th-18th Century

Saint Joseph and Christ Child, created by Mestizo artists part of the Andean art school, Cuzco School, unintentionally showcases a Mestizo representation of two important Catholic figures: Saint Joseph and Jesus Christ. Many details in this painting showcase this mixed identity. Although fair-skinned, both figures are draped in meticulously-crafted regalia, a nod to the clothing worn by Inca kings and icons. Pink, red, and white flowers are used throughout the painting, symbolizing purity, passion, and new beginnings. The various interpretations of these colors and their symbolism are what create such a nuanced and intense work of art.

Who is “Uncredited Mestizo Artist(s)” and why are they the artist of almost every piece in this exhibit? Many of the artists of the pieces in this exhibit were made by Mestizo (people who are a mixture of Spanish and Indigenous blood, a product of Latin American colonization) artists. In the case of the Cuzco School, the artists who created this art were all artists of indigenous blood who were forced to produce a narrative that was not only Spanish but also used to justify the genocide of their own people. On top of all this, the European Catholics running this school of artists never saw them as humans, did not get their names, and therefore never credited them.

What do you notice about these Peruvian paintings and those of Guaman Poma? Compare them.

Uncredited Meztizo Artist(s)

Black Christ of Esquipulas

18th Century

Esquipulas is a region located in Guatemala. The Indigenous people of Guatemala, alongside much of Central America, were the Maya. As the Spanish came to colonize Guatemala, they realized that many of the beings that the Maya worshipped were black. Ek Chuah, one of the most important Mayan deities, was perpetually depicted using black and dark colors. To the Spanish, this meant that the Mayan gods were demonic and were in need of replacement. They decided that the most efficient way to ease Catholicism into the Maya quotidian was by changing their icons to mirror their White ones. The Black Christ of Esquipulas was a product of this decision. These “Black Christs” replaced any trace of Ek Chuah and other black deities throughout Esquipulas, Guatemala, and other Central American countries.

In conversation with Saint Joseph and Christ Child, the Black Christ of Esquipulas is another Indigenous representation of European values. Both paintings capture two different Indigenous perspectives of Jesus Christ: a Mayan perception and an Inca perception. Visually unalike, each nation uses different ways of representing its own voice and ideologies within a symbol of brutal colonization. These two paintings also serve to reinforce the idea that indigeneity is not one group of people, but hundreds of nations, each with their own set of beliefs and outlooks on life. It is important to recognize that not all Indigenous people are the same.

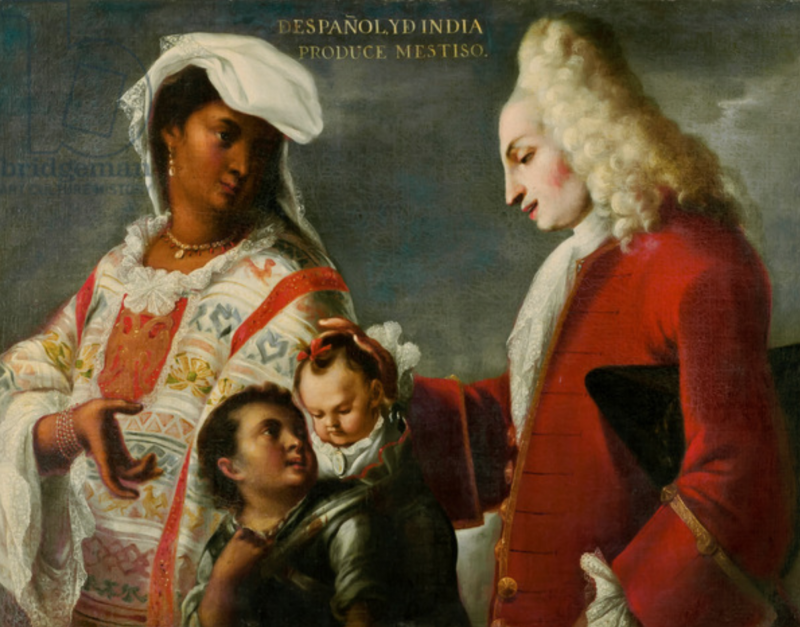

Juan Rodriguez Juarez

De Español, y de India Produce Mestiso

1725

Casta paintings, paintings that depicted various interracial pairings, were created in 18th-century Mexico. They would come in sets of 16 individual scenes. Each set would showcase a domestic view of a specific couple, occasionally accompanied by a child of their own. Each painting depicted a different interracial pairing with a different narrative to either promote or condemn that pairing. In a set, De Español, y de India Produce Mestiso, would be the first. This painting shows how life should be between a Spanish man and an Indigenous woman. This idealist scene relays feelings of structure and virtue within the context of colonization. The inclusion of a two happy children celebrates the idea of white men procreating with Indigenous women, by whatever means possible.

Of Spanish, and of Indian Produces Mestizo. “The reason why the very first painting of these sets tended to be a marriage between a Spanish man and an Indigenous or mestiza woman was to idealize that specific pairing; Spanish-Mexican culture deemed it the best, as the most favorable mixture of the time. In turn, this glamourization would justify the raping and interracial coupling between the White man and the native woman.” Excerpt from my essay, Las Castas Depravadas.

Uncredited Mestizo Artist(s)

De Negro y de India; Lobo

Late 18th century

A casta painting that depicts a pairing between a Black man and an Indigenous woman would appear towards the end of the 16 scene set. Commonly curated in rows or columns, this specific pairing was highly frowned upon. The generalized disdain for this relationship is clear in the ways that the subjects are depicted. The domestic violence showcased in De Negro y de India; Lobo serves as a warning against minority couplings such as Black and Indigenous. The frightened child supports this argument by saying that such a pairing is hurtful to the future of Mexico.

“Artists, who undoubtedly had access to resources like paint, materials, and skill, intentionally decided not to apply them to their depictions of Black people. Instead, these artists worked with a grayscale to paint them. There is an uncanny lack of human complexion in the Black people of casta paintings. This generalized decision is dire because it allows for the passive absorption of racism. If any person, from any time period, were to look at a casta painting that depicted a person of African descent, their brains would automatically detect a difference between that person and a Spanish person. What they might not realize is that this very difference, alongside the fact that people of color have been oppressed for centuries, not only tells a story of deceit but also of dehumanization.” Excerpt from my essay, Las Castas Depravadas.

Loïs Mailou Jones

Les Fétiches

1938

Flourishing throughout the Harlem Renaissance, Loïs Mailou Jones was an unsung pioneer of African themes and imagery appearing in Black American art. Les Fétiches marks an interesting departure from landscapes and the realist themes in Jones’ earlier works. This impressionist painting was her response to people who criticized the change in her style. According to Jones, "I had to remind them of Modigliani and Picasso and of all the French artists using the inspiration of Africa, and that if anybody had the right to use it, I had it, it was my heritage."

I empathize with all of the art historians who focus on Haitian art because it is virtually impossible to find any digital trace of Haitian art from the 16th century or earlier. Of course, when understanding this it is important to take into consideration Haiti's extensive and brutal history with France, but really, this is a problem of preservation. Because Haiti gained independence in 1801, it is plausible that the lack of Haitian art is due to an intentional erasure of indigenous Haitian culture by the French. Due to the lack of physical Taíno history available today, Haiti’s African roots are the only remaining history that we have. This erasure caused a surge in Haitian art created by Haitian-American artists in the mid-20th century. Where did all of Haiti’s art go?

Gabriel Bien-Aimé

Untitled

1989

Haitian artist Gabriel Bien-Aimé was an esteemed sculptor and a creative. After studying mechanics in Port Au Prince, he applied this knowledge to his artistry. He took much inspiration from Georges Liautaud, a famous Haitian artist who too worked with metal. Much of Bien-Aimé’s pieces are created from recycled materials such as steel oil drums. After gaining recognition, his work was showcased in various exhibitions around the world, such as the 1989 show at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Magiciens de la Terre, and the Picasso Primitif show at the Museé du Quai Branly -Jacques Chirac, Paris in 2017.

Georges Liautaud

Untitled (Metamorphosis)

1970

Georges Liautuad was one of Haiti’s most revolutionary artists and sculptors. Born in 1899, he lived 92 years of creativity and grace. Liautaud pioneered the use of recycled metal in art and influenced many sculptors who came after him. This sculpture depicts a schoolgirl surrounded by boy figures. At her feet is a bird that is facing the opposite direction from her. Although measuring 11.25 x 8.5 inches, this sculpture holds so much life and movement. Different senses are evoked from this piece, an idea that perpetuates through Haitian traditions.

Included to show the circulation of everlasting inspiration, the work of Gabriel Bien-Aimé and Georges Liautaud shows the life captured by Haitian artists. Used to protest one of the MoMA’s most controversial exhibitions, 'Primitivism' in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern” where in 1984 the museum found it to be a good idea to showcase cubist masterworks from Picasso next to Indigenous and African pieces. Inappropriately, the curators decided not to include the dates nor supporting information on the non-European pieces, deeming these spiritually-charged afterthoughts and static objects. In “Representing the Unseen” each of the African and Indigenous belongings is given its life back.

Rufino Tamayo

Girl Attacked by a Strange Bird

1947

Born in Oaxaca, Mexico, Rufino Tamayo was an important artist in the Latin American Cubist movement. Taking inspiration from his own Mexican identity, an identity rooted in cultural mixing and a flourishing surrealist history, Girl Attacked by a Strange Bird captures what it means to be Mexican. Depicted in the painting is a dark-skinned girl playing in a field. Unlike the work by Georges Liautaud, the bird in this painting is directly facing the girl. Towards the bottom of the piece is a figure of heads reminiscent of the humanoids in the work by Gabriel Bien-Aime.

Although artist Rufino Tamayo is not vocal about the African influences in his art, this influence is seen through the power of curation. Interestingly enough, many surrealist and cubist artists do not actively mention where their styles come from and say that it is solely theirs. While for many cases this is not true, it gets more complicated for artist Tamayo. Rufino Tamayo is a Mexican artist whose paintings embody the Mexican and Latino cultures and traditions. But what does Mexican culture consist of? Mestizaje. When you think of Meztisos, you often think of Indigenous and Spanish people only, eliminating the African identity. Rufino Tamayo protests this flawed idea by saying that the African identity can be and is a part of Mestizaje through his artwork.

Sergio Valdez and the Tzeltal Nation

El Mural de Taniperla

1998

This pictorial work, created by members of the Tzeltal nation and artist Sergio Valdez, was created to celebrate the inauguration of the self-proclaimed Zapatista Autonomous Municipality. This municipality was composed of territories under the rule of the Zapatistas. Contrary to popular belief, the Zapatista Autonomous Municipality did not seek to take over governments or power, but for Indigenous peoples to acquire governmental roles of authority in the then-current Mexican government. Their main focuses were on the education and health of their people and land. Seen in the mural are the people from this indigenous group fighting for their voices and the right to have power.

As beautiful as this mural is, its true grace lies in its creation. There is no one person who takes credit for the production of this work of art, but a nation. It is a collaborative effort, a collection of individual perspectives and identities. This is indigenous in its nature. There is no one anything, no god, no ruler, no artist. Everything is made by and for the people. I wonder how our world would look today if we practiced the ideologies of the people whose land this belongs to.

Mahku Movement

Untitled

2013-2025

In 2013, a group of indigenous artists, in Kaxinawá (Huni Kuin) Indigenous Territory, Acre, Brazil, a territory located alongside the border between Brazil and Peru, came together to form an artist group. Rooted in the myth about the passage between the Asian and American continents through the Bering Strait is the Mahku Movement, as all of their work is in some way connected to the larger significance of the myth. This painting depicts a large bird rising above a group of smiling people, all enclosed by a snake. The patterns used in the painting are a modern version of the Indigenous patterns of the Huni Kuin nation.

My close friend Lucía said something very interesting. During one of our conversations about this project, she noted that there is a general belief that indigeneity is antiquated, that indigenous populations only existed in history, they as a people are in the past, because colonizers killed them all. While it hurts me deeply to say that, for the most part, this is true, Indigenous people still live among us today. Although a severe minority with few rights, indigenous populations still have a voice and fight to make that voice heard. The inclusion of this piece from the Mahku Movement is to remind audiences that Indigenous people, indigenous artists, are here to stay.

Roberto Aizenberg

Figures or Persons in a Landscape

1953

Argentine painter Roberto Aizenberg was fascinated by the surrealist nature of Latin America found in early Indigenous and Latino art and literature. Depicted in this painting are two headless figures, one appearing to wear a dress and the other a robe. To contradict the foreground, the background is monotonous. The clothing worn by the two figures is composed of geometric patterns that mimic those of Indigenous royals of precolonial Latin America.

Before you read the end of this, I want you to take a look at the two Guaman Poma pieces at the very beginning. What do you see? Do you notice any similarities?

You noticed that the regalia of both this Aizenburg piece and the kings and mothers of Guaman Poma’s people are very similar.

Now ask yourself, why do they look so similar?

Is it because Roberto Aizenberg, an Argentinian artist, took inspiration from Indigenous bodies to be the foundations of his supposed “surrealist” and “dreamlike” scene?

Who is to say that this work of art is surrealism when there is direct proof that it was a reality for an entire civilization?

When does this cycle of colonization stop?

Works Cited

“Black Christ of Esquipulas.” Jaime Eguiguren, https://jaimeeguiguren.com/usr/library/documents/main/black-christ-of-esquipulas.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2025.

“El Divino y lo Recatado / The Divine and the Demure.” Klara Deane, https://klaradeane.substack.com/p/the-divine-and-the-demure. Accessed 25 June 2025.

“Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala.” Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Felipe-Guaman-Poma-de-Ayala. Accessed 25 June 2025.

Gabriel Bien-Aimé. Indigo Arts Gallery, https://indigoarts.com/artists/gabriel-bien-aim. Accessed 25 June 2025.

Georges Liautaud. Artsy, https://www.artsy.net/artist/georges-liautaud#:~:text=Haitian%2C%201899%E2%80%931991&text=Georges%20Liautaud%20was%20the%20originator,(MoMA)%20in%20New%20York. Accessed 25 June 2025.

La nueva corónica y buen gobierno. By Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala.

“Les Fétiches.” Smithsonian American Art Museum, https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/les-fetiches-31947. Accessed 25 June 2025.

MAHKU: Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin. La Biennale di Venezia, https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2024/nucleo-contemporaneo/mahku-movimento-dos-artistas-huni-kuin. Accessed 25 June 2025.

“Mural de Taniperla.” Wikipedia, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mural_de_Taniperla. Accessed 25 June 2025.

“Municipios Autónomos Rebeldes Zapatistas.” Wikipedia, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Municipios_Aut%C3%B3nomos_Rebeldes_Zapatistas. Accessed 25 June 2025.

“Standing Female Figure.” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/en-GB/objects/687. Accessed 25 June 2025.

“Standing Male Figure.” Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/objects/679. Accessed 25 June 2025

Add comment

Comments